A Historic City Church Looking to the Future

The First Presbyterian Church in the City of New York celebrated its three hundredth birthday in 2016. From its first home in 1716 in a small building on Wall Street in the center of the young city, it has grown and prospered to become a landmark on lower Fifth Avenue. Throughout its history, whenever there was a choice to be made, it has emerged on the side of tolerance and open-mindedness.

On a January Sunday in 1707, Francis Makemie, the Scots-Irish clergyman who was instrumental in establishing the Presbyterian Church in the colonies, preached publicly to a small group in a private home in New York. This unlicensed act gave grounds for his arrest; it was the Anglican Church that had the right to hold public worship. Makemie was acquitted and moved on, but what he had set in motion took permanent shape.

1716: The Beginning

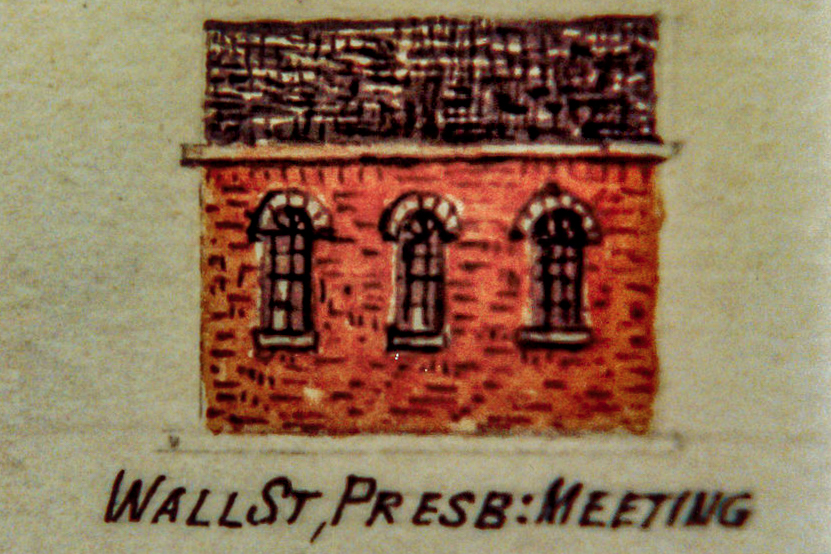

In 1716, a group of about eighty New York dissenters organized themselves into a congregation of the Church of Scotland, and build a simple structure on the north side of Wall Street east of Broadway. The first worship service in the “Church on Wall Street” was held in 1719.

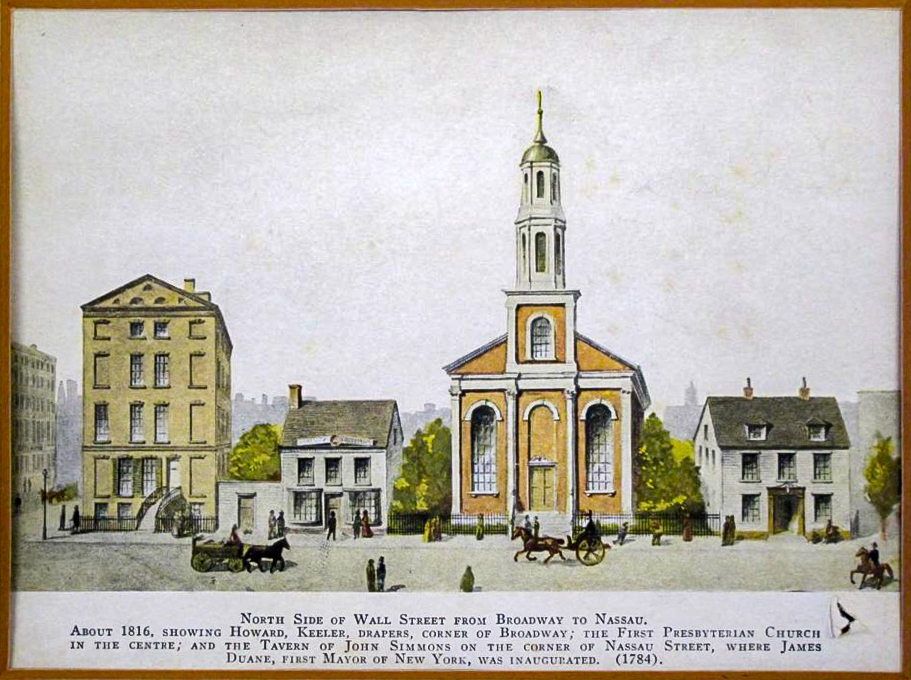

Division between the more conservative Scots and more progressive English members inhibited growth until the congregation was revitalized by the First Great Awakening, an evangelical movement of the 1730s and 40s. The Wall Street Church was enlarged in 1748, and a steeple and bell were added. Still more meeting space was needed when the congregation grew to three hundred, and in 1768 the “New Church,” or the “Brick Church,” was built a little further north, at the corner of Nassau and Beekman streets, near the site of the present City Hall Park. The single church held services at two sites.

1775: The War of Independence

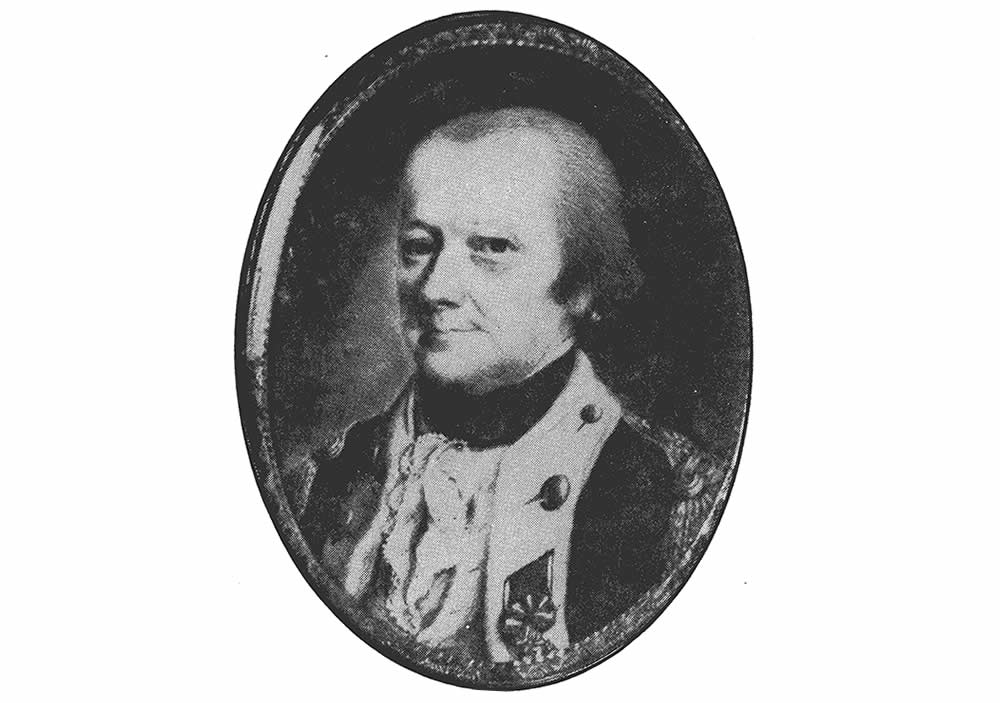

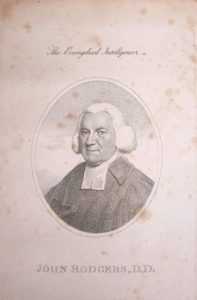

The War for Independence divided Presbyterians, whose churches in the colonies were independent from Europe, from Anglicans, who remained tied to England by their church structure. Most Anglicans supported the King and Parliament; most Presbyterians opposed. The influence of the dissenters was sufficient for the War to be called “the Presbyterian rebellion.” The Reverend John Rodgers, pastor of the Wall Street Church from 1765 until 1811, was a zealous patriot, and many of male members of the congregation served in the Continental Army. During the seven years, 1776 to 1783, when British troops occupied New York, the church buildings were vacated and families with sympathies for the colonial cause sought safety out of the city.

When the British departed the city after the War was over, they left the Presbyterian structures badly damaged. Tradition holds that they stabled their horses in the Wall Street Church. But with differences settled, the Anglicans loaned their chapels for worship while repairs were made. The Brick Church reopened in 1784 and the more badly damaged Wall Street Church, the following year. More importantly, the state of New York made the Presbyterian Church the first religious organization to receive a charter, and this permitted it to be incorporated as the First Presbyterian Church in the City of New York, a name that made its informal name, “First Church,” possible.

Forty years later there were several dozen Presbyterian churches in New York. The Wall Street Church and its satellites had split into separate bodies, and other churches had organized, merged and split as well. In 1811 the structure on Wall Street that still housed “Old First” was found to be structurally compromised, and it was totally rebuilt. In 1835 the Great Fire destroyed much of lower Manhattan, the city of New York as it existed in that day.

The Church on Lower Fifth Avenue

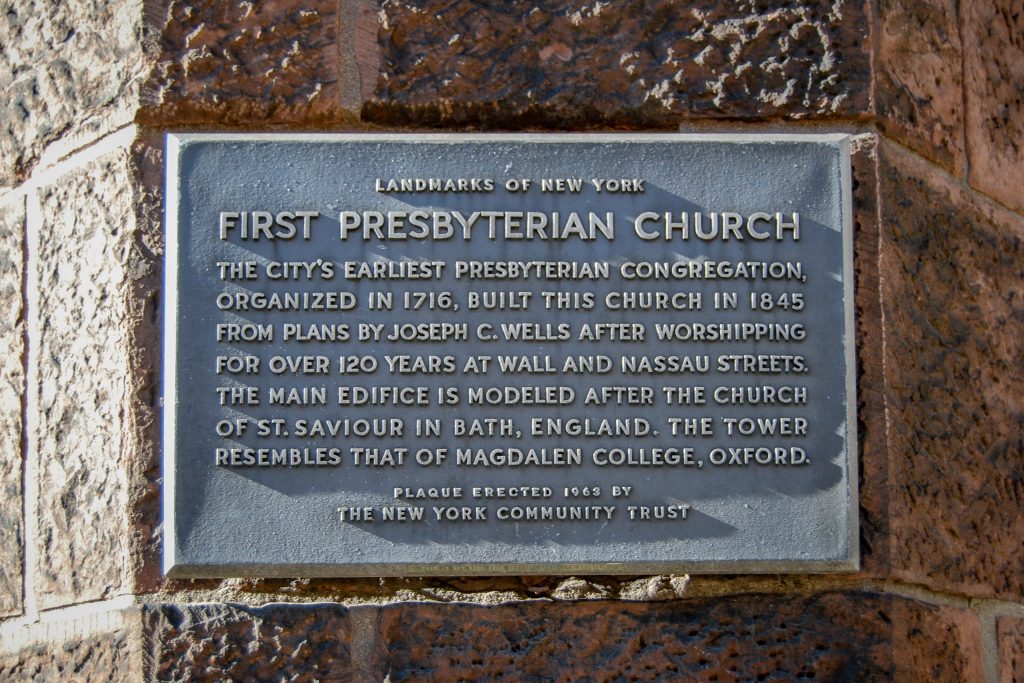

The population was already shifting north, and Old First at its downtown location had suffered from declining membership. The church followed the population uptown to the flourishing neighborhood near Washington Square, and a new church was built in the Gothic style on Fifth Avenue between Eleventh and Twelfth Streets. The eighteenth and nineteenth Century burial vaults were transferred from the Wall Street Church” and relocated under the new church’s north lawn. The congregation moved into its new home in 1846.

1892: Charles H. Parkhurst

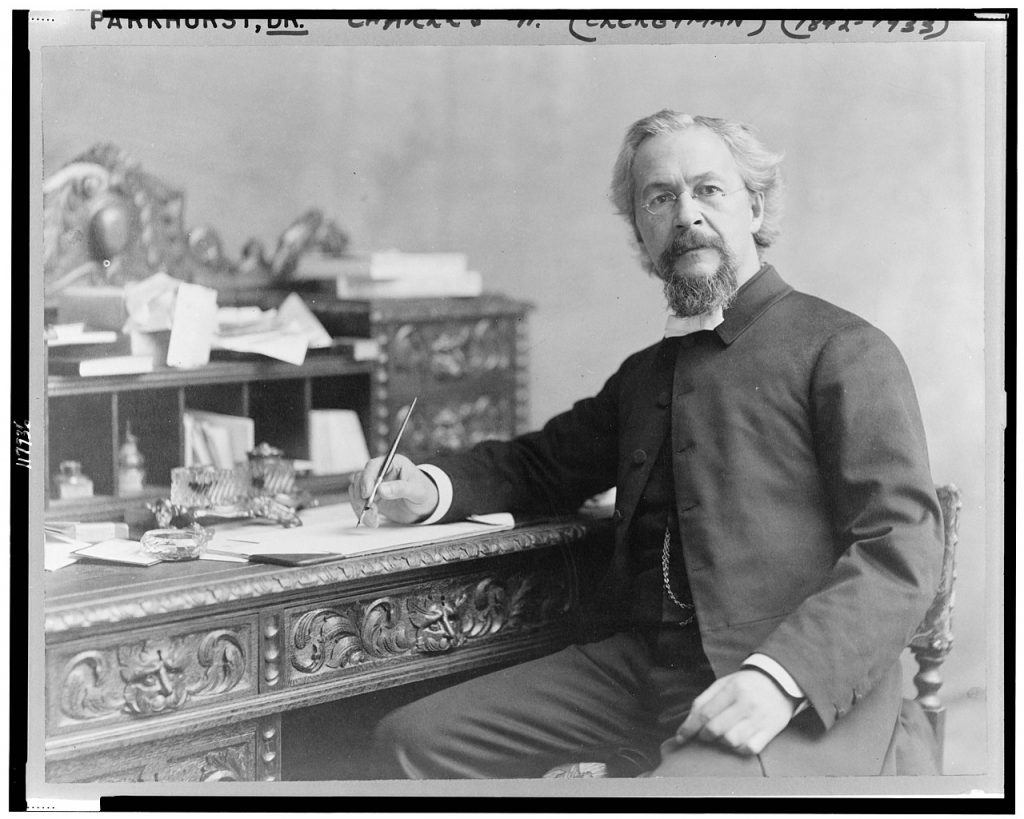

Within the same decade two other Presbyterian churches were established in the affluent neighborhood: the University Place church at Tenth Street and University Place and the Madison Square church a Twenty-fourth Street and Madison Avenue. Charles H. Parkhurst, the crusading pastor of The Madison Square Church, successfully challenged Tammany Hall and the corrupt city government in the 1890’s. He used the pulpit to chastise the immorality of the gambling houses and brothels that the police tolerated.

1918: The Merger of Three Churches

But at the beginning of the twentieth century the wealth that had supported the three churches was moving on north once again, this time up Fifth Avenue. They responded by merging as equals in 1918. This produced the rather cumbersome legal name of the present institution: “First Presbyterian Church in the City of New York — Founded 1716, Old First, University Place, Madison Square Foundation.” The Fifth Avenue structure was chosen to house the new church. No one church absorbed another, and the individual histories of the three were absorbed into the history of the new First Church.

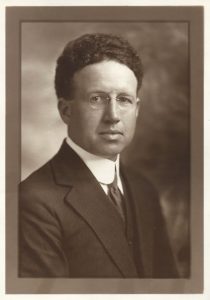

1919: Harry Emerson Fosdick

First Church was again in the news when Harry Emerson Fosdick, a central figure in the “Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy” of the time, filled its pulpit in the position of “preaching minister.” He preached that science and faith were not incompatible. Fosdick’s sermons packed the church from 1919 until 1924, when conservative elements in the national church forced him to leave. In giving him the pulpit, First Church was again endorsing a position that looked to the future and not the past.

1950s/1960s: Pioneering Education

First Church has continued to support progressive causes. In the nineteen thirties it endorsed the ordination of women. It was a pioneer in pre-school education in the fifties and then in the early childhood special education. In the sixties its pastors supported the election of the first Black moderator of the national church’s General Assembly. It was led during this time by the unusual co-pastorate of John O. Mellin and John B. Macnab.

1990s and Beyond: An Open Door

J. Barrie Shepherd became pastor in 1992 and brough new energy to the campaign for openness. First Church led in the struggle to include all, regardless of sexual orientation, in every level of church responsibility.

2001: 9/11

Jon M. Walton, who followed Shepherd as pastor, preached his first sermon at First Church on Sunday, September 9, 2001. Two days later planes flew into the World Trade Center. When the mayor closed the city below Fourteenth Street after the attacks, the church’s location made it a refuge for those in need of comfort. Its doors were open to all who came looking for reassurance.

The church still stands on the spot where it came to rest in the mid-nineteenth century, able to change with the neighborhood, with no need to follow its population’s migration through the city. It remains a fixed point in Greenwich Village. And as always in the past, it looks now to the future with its pastor, Greg Stovell.

Presbyterians, led by their activist pastor, John Rodgers, were active participants in the political events that led to the War of Independence. Preeminent were three lawyers, Trustees of the Wall Street Church: William Livingston, William Smith Jr., and John Morin Scott. Merchant Alexander McDougall, another church member, was the street leader of the group of sailors known as the “Sons of Liberty,” who demonstrated against the implementation of the unpopular Stamp Act of 1765. Loyalists named the rioters a “Presbyterian junta.”

McDougall was arrested twice in 1770, and he made himself a political martyr by refusing bail. His supporters escorted him ceremoniously to jail and turned his internment into political theater. Since he was the Clerk of the Board of Trustees of the Wall Street Church, their meetings took place in jail in January and February of 1771. After being incarcerated for a total of five months, McDougall was acquitted. He was made responsible for the defense of the city in 1775 once war became inevitable. He rose to become a major general in the Continental Army and was a delegate to the continental congress.

The Trustees of the Presbyterian Church were spending so much time on political matters that many of their meetings had to be adjourned for lack of a quorum. They met last in January of 1775, and the Session met for the last time in December of that year. With the dispersal of the civilian congregation, the New York church ceased to be active. George Washington and his force were defeated in the Battle of Brooklyn and retreated, and the British arrived in New York in August of 1776. The occupying troops caused serious damage to the Presbyterians’ Wall Street building, using it first as a barracks and then as a stable for their horses. The Brick Church building became a hospital.

Pastor John Rodgers was a prominent figure both within the church and in the community during this period. The British put a price on his head. He would later serve as a chaplain in the Continental Army. A dynamic preacher, Rodgers normally spoke without notes, but written versions of some sermons exist. Two came to light only in 2003, one dated to January 1776 and the second to July of that year. In them he exhorts the young men of his congregation to fight for liberty: “Let a spirit of patriotism fire your breath,” he wrote and, “Many have already dressed themselves in military array and taken the field, choosing rather to risk their lives in the cause of liberty, than to resign their privilege and live in slavery.” He later sent a copy of a sermon that he delivered in 1783 to George Washington. It shows him openly favoring the federalist argument that was before the nation’s founders at that time, stating it as “indispensably necessary that the federal union of these States be cemented and strengthened.”

When First Church moved from its original Wall Street location to its current site on Fifth Avenue, the building committee decided to build in the Gothic style and selected Joseph C. Wells, an English immigrant who was one of the founders of the American Institute of Architects, as architect and J.G. Pierson as builder for the new church. The sanctuary is said to be modeled on the Church of St. Saviour at Bath, England, and the crenellated central entrance tower on the Magdalen Tower at Oxford. The dressed ashlar tower of brownstone is embellished with a Gothic revival tracery of quatrefoils.

A reporter of the New York Herald described the interior of the newly built church: “The interior of the edifice presents a novel and yet a very agreeable and impressive aspect. It is of the perpendicular Gothic Style, without columns to sustain the long extending arch, which makes the seats in a remarkable degree available and unobstructed. This is a new feature in modern architecture. The slips [pews] are of black walnut of native growth, most beautifully and tastefully carved.… The ceiling is formed by a system (if it may be so called) of groined arches, with intersecting ribs and pendants forming the keystone of this massive structure.” (January 12, 1846).

The First Presbyterian Church in the City of New York celebrated its three hundredth birthday in 2016. From its first home in 1716 in a small building on Wall Street in the center of the young city, it has grown and prospered to become a landmark on lower Fifth Avenue. Throughout its history, whenever there was a choice to be made, it has taken its stand on the side of tolerance and open-mindedness.

On a January Sunday in 1707, Francis Makemie, the Scots-Irish clergyman who was instrumental in establishing the Presbyterian Church in the colonies, preached publicaly to a small group in a private home in New York. This unlicensed act gave grounds for his arrest; it was the Anglican Church that had the right to hold public worship. Makemie was acquitted and moved on, but what he had set in motion took permanent shape when, a few years later, in 1716, a group of about eighty New York dissenters organized themselves into a congregation of the Church of Scotland. They raised funds to buy a property and build a simple structure on the north side of Wall Street east of Broadway. The first worship service in the “Church on Wall Street” was held in 1719.

Division between the more conservative Scots and more progressive English members inhibited growth until the congregation was revitalized by the First Great Awakening, an evangelical movement of the 1730s and 40s that rejected past rigidity and strict doctrine and emphasized a theology of personal conviction, the direction that Protestantism would take. The Wall Street Church was enlarged in 1748, and a steeple and bell were added. Still more meeting space was needed when the congregation grew to three hundred, and in 1768 the “New Church,” or the “Brick Church,” was built a little further north, at the corner of Nassau and Beekman streets, near the site of the present City Hall Park. The single church held services at two sites.

Charles H. Parkhurst, pastor of the Madison Square Presbyterian Church at the end of the nineteenth century, already had a reputation for dynamic preaching when he began his crusade against corruption and vice in 1892. He used his pulpit to attack city officials and the police force, accusing both of being no more than tools of Tammany Hall, the Democratic political machine, and of tolerating illegal drinking and houses of prostitution. Unsavory places of business had been moving into the vicinity of his church, and he considered them harmful, especially to the young men of his congregation. In a scathing sermon on Valentine’s Day, he castigated members of the city administration as “a lying, perjured, rum-soaked, and libidinous lot.”

Parkhurst’s controversial sermon put his church in the news, catching the attention of the government and the press. Challenged to provide proof of his charges, he hired a lawyer, acquired a youthful assistant, and disguising himself in filthy old clothing, visited saloons, gambling dens and houses of ill repute in order to collect hard evidence. He returned to the pulpit a month later (March 13) with a stack of affidavits in hand and a long list that named the offending establishments. A large crowd was waiting in the church for his report.

The following year, 1893, saw Parkhurst broadening his attack, moving beyond the identification of the individual saloons, brothels and gambling houses, to making corrupt politicians the object. His work enjoyed a degree of success when the election of 1894 returned a Republican as mayor, an opponent of the candidate endorsed by Tammany Hall. The new mayor, William J. Strong, appointed Madison Square parishioner Teddy Roosevelt to head of the New York Police Board, and it was from this position that Roosevelt launched his political career. But it would be more than another half century before the influence of Tammany Hall was completely broken. Parkhurst himself reported that “the Tammany tiger was not dead yet—had just had its tail badly twisted.” But it had been checked, and Parkhurst’s influential pulpit had been instrumental.

Despite the temptation to move their congregations uptown, the three churches with homes north of Washington Square considered it important to maintain a single strong downtown church and chose to merge instead. Charles Parkhurst hoped that “there would be established an institution so securely planted as to be proof against the effect of shifting populations and all other adverse influences that might assert themselves for generations to come.” Each of the three contributed its endowment to the joint project, and each had a particular advantage to offer: Old First provided the best location with its Fifth Avenue address; besides, a recent zoning ordinance that reserved the Avenue south of Fourteenth Street for residential use provided protection. The University Place Church contributed the largest and most active congregation. The Madison Square Church added considerable wealth from the sale of its valuable property. Furnishings were transferred to the Fifth Avenue site as tangible indicators of the union: The pulpit that stands in First Church came from the University Place Church, the baptismal font from Madison Square.

Old First was closed in the summer of 1918 in order to prepare it for its role as the home of the consolidated church. The first service took place on November 3, 1918. In order that it not appear that the identity of any one church was absorbed into that of another, the three pastors, all of retirement age, resigned, Parkhurst from Madison Square, George Alexander from University Place and Howard Duffield from Old First. The new independent First Church would be free to choose its own pastor. It was now a much larger institution, and responsibilities were sensibly divided. Dr. Alexander was chosen as senior pastor, young Thomas Guthrie Speers of Madison Square became an associate pastor responsible for administration, and Harry Emerson Fosdick, a Baptist professor at Union Seminary, would do most of the preaching.

Parkhurst called the new church the “Presbyterian Cathedral of New York City.”

Christianity had become troubled by the conflict between Biblical creation and the new knowledge from Darwin’s discoveries. Harry Emerson Fosdick was a prominent spokesman for the anti-fundamentalist theological position that faith and science could co-exist. A pacifist and promoter of the League of Nations, he had joined the faculty of Union Theological Seminary in 1911 and was teaching there when he was invited to join the ministerial team of the newly organized First Church as “preaching minister.” He was a captivating preacher, and overflow crowds packed the church to hear him advocate tolerance and the liberal position. But as an ordained Baptist minister Fosdick was an odd person to find in a Presbyterian pulpit. He did not become a Presbyterian and so remained a guest in the church, and this was a factor in the controversy that surrounded his tenure.

In 1922, Fosdick preached a sermon with the title, “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” It was a reasoned espousal of the view that science had a place beside faith. Widely circulated, it became a central document of the modernist movement, attracting the particular attention of church conservatives, among them the politician, William Jennings Bryan. Since Fosdick was not a Presbyterian he could not be reprimanded through the channels of church governance, but his position could be. Asked to become a Presbyterian or resign his First Church pulpit, he chose the latter. He submitted his resignation in 1923, but the Session showed its strong support and refused to accept it. The next year, however, he petitioned successfully, and he left First Church in 1925. His farewell sermon was so eagerly anticipated that, according to church lore, the marble floor of the central aisle in the sanctuary developed a crack from the weight of the over packed balconies. The crack is visible today.

From First Church Fosdick went to the Park Avenue Baptist Church where John D. Rockefeller, Jr., was a member. Rockefeller was instrumental in financing the establishment of the interdenominational Riverside Church in Morningside Heights. Fosdick’s liberal voice could be heard there from 1930 until 1946 when he retired.

Harry Emerson Fosdick Lectures

Learn more about Harry Emerson Fosdick’s ministry and influence on American Protestantism in a set of lectures written by archivist David Pultz:

The 1890s saw great changes in society: The industrial revolution and the changing of the United States from an agrarian society to an urban one.

The 1890s were also a decade of intellectual upheaval. Between the depression of 1873 and the First World War, many of the time-honored suppositions were being questioned. Darwin’s theory of evolution was one of the most prominent new ideas, challenging the authority of the Bible and the presumption of its inerrancy.

A working definition of Modernism, Liberalism and Fundamentalism in the American Protestant context is necessary to understand the basics of the conflict.

Traditionalists, later known as Fundamentalists, adopted a five-point declaration at the 1910 General Assembly that all candidates for ordination had to affirm. These five points were of course a reaction to the growing acceptance within Protestantism and, specifically the Presbyterian Church, of a more liberal interpretation of the Bible.

The five Fundamental points are:

1.The inerrancy of the Bible

2.The virgin birth of Christ

3.Christ’s substitutionary atonement

4.Christ’s bodily resurrection

5.The authenticity of Christ’s miracles

Other Christian groups adapted the five points with point two often becoming the deity of Christ rather than his virgin birth.

Many lists ended with Christ’s premillennial second coming, instead of his miracles, as the fifth point.

By the 1920s the five points had become called the five fundamentals and had become a rallying cry for conservative Christians across a broad spectrum.

As Jack Rogers, in his book Presbyterian Creeds: A Guide to the Book of Confessions, states: “This was especially true for the growing movement of independent Bible conferences, Bible schools, and independent churches influenced by Dispensationalism. This movement majored in literalistic, futuristic, interpretation of biblical prophecy which announced Christ’s imminent return following a very specific and complex timetable of attendant events. Dispensationalists also taught that all the traditional institutional churches had grown worldly and denied fundamental doctrinal beliefs.”

Modernism may be defined as a method of interpreting Christian scripture and tradition, but not a particular set of beliefs. Modernizers can be found in every period of Church history and Christian Communions. But when we speak particularly of Protestantism in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, we see a conviction in the new scientific knowledge and the most recent Biblical historical research. An application of this new knowledge presents real issues for Christians. As a result, according to Modernism, the task of interpretation must be carried forward if the saving truth of the gospel is to be understood in its relevance to contemporary life.

As for Liberalism, Daniel D. Williams, former Professor of Systematic Theology at Union, says, “It might be said with some accuracy that all theological liberals were modernists; but not all those who used modernist methods of interpretation shared the faith of the liberal theology, especially its optimistic estimate of human nature.”

Further, he says: “Liberals have taken a positive attitude toward the achievements of democratic culture and have generally stressed the ethical imperatives in the gospel.”

Williams also quotes the German theologian Adolf Harnack, who, near the turn of the century, had this classic definition of Liberal theology: “Firstly, the Kingdom of God and its coming. Secondly, God the Father and the infinite value of the human soul. Thirdly, the higher righteousness and the commandment of love.”

In the social gospel movement Walter Rauschenbusch, who was professor of Church History at Rochester Theological Seminary in the early part of the century, became a chief interpreter and prophet. His concept of social sins involved society as a whole (e.g., poverty, child labor, poor working conditions, etc.), and held that these needed to be urgently addressed. To Rauschenbusch and his followers, Christian social activism and advocacy was a compelling Biblical ethic.

The Fundamentalist / Modernist conflict began with the Charles A. Briggs heresy trial. The trial was a reaction from conservative traditionalists to Briggs’s address on January 20, 1891, at Union Theological Seminary on, “The

Authority of the Holy Scriptures.” It was an address inaugurating the opening of the new Department of Biblical Theology.

Briggs was a professor of theology at Union, and he attacked “Traditionalism,” later known as Fundamentalism, and espoused an interpretation of the Bible in the light of the “Higher Criticism.” The Higher Criticism was a method of investigating facts based on scientific investigation, inductive research, and a relative system of values.

Carl E. Hatch, in his 1969 book The Charles A. Briggs Heresy Trial, lists three main factors that stand out as transforming American Protestant theology: Darwin’s theory of biological evolution, Higher Criticism, and the study of comparative religion. Hatch further makes the point that the impact of Darwin’s theory of evolution on American Theology is well known, but that of Higher Criticism and comparative religion much less so.

Briggs had studied in Germany where the methods of Higher Criticism had begun. Julius Wellhausen had perhaps the most influence upon American theologians. He is known as the Father of Higher Criticism. Briggs’s favorite teacher at the University of Berlin, which he attended, was A.I. Dorner, a disciple of Wellhausen.

Charles A. Briggs was born in New York City on January 15, 1841. He attended the University of Virginia, but in his Junior year, 1861, returned home because the Civil War was imminent. After joining the Union Army for about a year and helping defend Washington D.C., he was released to go home, for reasons not known. He entered Union Seminary and graduated in 1863. After graduation he tried helping his father in his merchandising firm in New York, but quickly decided it was not for him. Briggs then matriculated to the University of Berlin. It was a turning point in his life.

After completing his studies, he returned to New York and in 1870 was ordained a Presbyterian minister. He served for a time at a church in Roselle, NJ, but soon found that it, too, was not to his temperament. In 1874 an invitation came to teach at Union. He was professor of Hebrew and Cognate Languages. Although he found it much more rewarding to teach than be a pastor, the subject did not afford him much opportunity to approach Biblical criticism.

Briggs had wanted to forcefully introduce the German theology into this country, but “How to do it?” was his question.

Since Union was under the control of the General Assembly, and most Presbyterian clergy were conservative and therefore disposed against the German Higher Criticism, Briggs had to be careful in what he wrote in religious publications and what he taught in the classroom.

Briggs then maneuvered to create a new department, using the Higher Criticism. But instead of using that term, he used the euphemistic “Department of Biblical Theology.” Briggs, of course, was to be head of the department.

Little opposition was encountered from Union faculty or administration for the creation of the new department. For, despite generally conservative clergy within the Church, Union’s faculty and administration at the time were more progressive and favorably inclined toward the German theology. Charles Butler, chairman of Union’s board of directors, had been a boyhood friend of Briggs and supported the plan wholeheartedly. In April of 1890 Union received $100,000 in bequest money for the new department. The board voted in the new department unanimously in November of that same year.

On January 20, 1891, Briggs gave his address inaugurating the new department.

The speech cheered Briggs’s students. They enthusiastically applauded him at points, but it angered the invited conservative guests and clergy.

The speech is very much a polemic, attacking beliefs about the Bible that the Victorians held as eternal and inviolable.

Briggs began by asserting that there were three, not one, great sources of divine authority. The first was the institutional Church, the second was reason, and the third the Bible.

“But of all three ways,” Briggs said, “no one of these has been so obstructed as the Holy Bible.” He argued that the authority of the Bible had been so wrapped in dogma and protective creeds, that “The whole trouble with the Bible today is that it has been treated as if it were a baby, to be wrapped in swaddling clothes, nursed, carefully guarded lest it should be injured by heretics and skeptics.”

As Carl Hatch relates in his book, “The net effect of this,” according to Briggs, “was to shut out the light of God, to obstruct the life of God, and to fence in the Bible, thus rendering the Bible useless.”

Briggs next attacked superstition as keeping people from the Bible. “We are accustomed to attach superstition to the Roman Catholic Mariolatry and the use of images, and pictures and other external things in worship. But superstition is not less superstition if it takes the form of Bibliolatry.” Mariolatry is idolatry of the Virgin Mary. Bibliolatry is idolatry of the Bible.

“The second barrier,” said Briggs, “keeping men from the Bible is the dogma of verbal inspiration.” These comments, reports Hatch, were “extraordinarily incendiary because the doctrine of verbal inspiration was (and still is) one of the dearest tenets of evangelical Protestantism.”

In Briggs’s third barrier, he maintained that the idea that the Scripture is inerrant is false. “The Bible itself nowhere makes the claim that it is inerrant,” said Briggs.

The fourth barrier, said Briggs, was the assumption that the authenticity of the Bible was founded upon the belief that holy men of old had written the various books.

Said Briggs: “When such fallacies are thrust in the face of men seeking divine authority in the Bible, is it strange that so many turn away in disgust? It is just here that the Higher Criticism has proved such terror in our times. Traditionalists are crying out that it is destroying the Bible, because it is exposing their fallacies and follies. It may be regarded as the certain result of the science of the Higher Criticism that Moses did not write the Pentateuch or Job; Ezra did not write the Chronicles, Ezra or Nehemiah; Jeremiah did not write the Kings or Lamentations; David did not write the Psalter, but only a few of the Psalms; Solomon did not write the Song of Songs or Ecclesiastes, and only a portion of the Proverbs; Isaiah did not write half of the book that bears his name. The great mass of the Old Testament was written by authors whose names or connection with their writings are lost in oblivion.”

At last Briggs ended his shocking pronouncements with this vigorous exhortation:

“We have undermined the breastworks of Traditionalism; let us blow them to atoms. We have forged our way through the obstructions; let us remove them now from the face of the earth, criticism is at work everywhere with knife and fire! Let us cut down everything that is dead and harmful, every kind of dead orthodoxy, every species of effete ecclesiasticism, all mere formal morality, all those dry and brittle fences that constitute denominationalism, and are barriers to church unity.”

“Let us burn up every form of false doctrine, false religion, and false practice. Let us remove every incumbrance out of the way for a new life; the life of God is moving throughout Christendom, and the spring time of a new age is about to come upon us.”

With this blistering attack upon the traditionalists, Briggs faced considerable reaction from within the Church in the form of open theological warfare. Before this, the Higher Criticism posed only a vague threat to the traditional theology. Briggs, in one speech, had moved it full throttle into a formidable threat to upset the prevailing orthodoxy.

It is interesting to note the overwhelmingly positive reaction the students had to Briggs’s speech and theological position. His students were about the same age as Harry Emerson Fosdick was at that time, and as you may remember, Fosdick reports that as a student at Colgate he himself rebelled against the old orthodoxy.

The initial public reaction to Briggs and his theological outlook was cool, but in many newspaper editorials there was a sense of outrage and dismay.

In April of 1892 the Presbytery of Cincinnati petitioned the General Assembly to take action against Briggs. By the time of the General Assembly in May, over seventy presbyteries, mostly from the Midwest, registered disapproval with the Assembly over Briggs’s teachings.

Most wanted the Assembly to order Union to remove Briggs, a power the Assembly had by the Compact of 1870 which had adjoined Union to other Presbyterian seminaries. The Compact clearly stated that the Assembly had power over the accepting or rejecting of professors.

The Union Faculty was solidly behind Briggs. Most favored the German Higher Criticism and rallied behind Briggs. Union alumni were also invited to join in the defense of Briggs. A solid majority of them did. One thing this showed was how much the higher criticism had penetrated into certain circles of American religious thought, despite an era generally marked by conservatism.

At the May General Assembly in Detroit, the Committee on Theological Seminaries, made up entirely of conservatives opposed to Briggs, voted to recommend removing Briggs as chair of the new Department of Biblical Theology.

The Cincinnati Presbytery even tried to organize a boycott by forbidding students of the Midwest to enter Union. The ploy eventually failed because it helped Union gain even greater notoriety for its theological position, thereby attracting more students, especially from New England. Union was now seen at the level of Yale and Harvard Divinity Schools.

At the same time, the Midwestern Presbyteries in 1891 put pressure on the New York Presbytery to bring a heresy charge against Briggs. In May that year a committee of inquiry, involving both liberals and conservatives in the Presbytery, recommended prosecution of Briggs.

By November of 1891 a trial had started. Briggs acted as his own counsel, making a brilliant opening statement that shifted the focus of the trial away from him personally to focus on the new theology. The trial was seen publicly as a forum on this theology, not on the heresy of Briggs’s teaching. Briggs was acquitted of heresy by a 94-39 vote.

Briggs was retried on appeal of the Portland, Oregon Presbytery, and again acquitted. However, at the General Assembly of 1893 he was suspended from the Presbyterian Church.

Meanwhile, Union separated from the Presbyterian Church over this case and retained Briggs as professor until his death in 1913.

Carl Hatch writes, “Although Briggs’ inaugural address did not actually begin a new era in American theology, biblical study in this country has never been the same since that provocative discourse.”

Fundamentalists and Liberals lived in tension in the following years. Presbyteries mostly in the Midwest and West were conservative. Those in the East were more progressive.

One area of tension was in the field of foreign missions. It was in 1921 that Fosdick went to China to ease tensions between missionaries representing churches from both sides of the fence. It was apparently the Fundamentalists that primarily wanted to be separate from their more liberal counterparts.

Reinhold Niebuhr, as a Midwesterner, saw the old traditionalist religion as a kind of rough and ready theology for the American frontier of the 19th century that had hardened into a graceless one for the 20th century.

In May 21, 1922 Fosdick preached “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” He writes in his autobiography, “It was a plea for tolerance, for a church inclusive enough to take in both liberals and conservatives without either trying to drive the other out.” Soon after the sermon, a man named Ivy Lee, a publicist and Presbyterian, asked Fosdick for permission to reprint the sermon in pamphlet form. Fosdick gave him permission and Lee mailed copies to every Presbyterian clergy in the country. A tremendous controversy ensued, with Fundamentalists within the Presbyterian Church, led by William Jennings Bryan, calling for Fosdick’s removal at the General Assembly of 1923.

In the meantime, Clarence E. Macartney, a minister from Philadelphia, preached a response to Fosdick, titled “Shall Unbelief Win?”

That General Assembly produced a resolution directing the New York Presbytery to direct First Church to conform to the Confession of Faith in its preaching and teaching. Fosdick handed in his resignation, but it was rejected by the Session. At the 1924 General Assembly, with Macartney as moderator and Bryan as vice moderator, Fosdick’s preaching remained an issue, and a compromise was finally struck between the two factions, asking Fosdick to regularize his position at First Church by becoming a Presbyterian minister. He refused, and in October of that year the Session accepted his resignation.

Also in that year, 13 percent of the ministers of the Presbyterian Church signed a document called the Auburn Affirmation. It stated that the Five Fundamentals, which the General Assembly had reaffirmed the previous year, went beyond the facts which the Scripture and the Westminster Confession obligated them.

Fosdick’s last sermon at First Church was on March 1, 1925. It was the same year as the Scopes trial in Dayton, Tennessee, in which William Jennnings Bryan came to national prominence.

In 1923, J. Gresham Machen’s book Christianity and Liberalism was published, adding fuel to the fire. It proclaimed that liberal Christianity was “a different religion” and he attempted to argue that it sprang from different roots. Consequently, he advocated a split within the Presbyterian Church along theological lines of ideology.

Machen was a professor at Princeton Theological Seminary. His aggressively militant view contrasted as polar opposite to the one to which Fosdick expressed.

As Jack Rogers says in Presbyterian Creeds, by 1925 “there were identifiable political parties within the Presbyterian Church. One was composed of theological liberals, who believed in an inclusive church, containing any who wished to belong. Opposed to them were doctrinal fundamentalists, who argued for an exclusivist church composed only of those who agreed with the five fundamental points. The largest group, though least well organized, was made up of moderates, who were theologically conservative but were inclusivists for the sake of the peace, unity, and mission of the church.”

Charles R. Erdman, a professor of practical theology at Princeton was elected Moderator of the General Assembly of 1925. Erdman was a moderate. He proposed a Special Theological Commission to study the state of the Church.

In 1927 the commission issued its final report, saying that no one, not even the General Assembly, had the right to single out doctrines such as the five points and determine a particular interpretation of them to be “essential and necessary” for all. They affirmed that only the Judicial process of the church – i.e., heresy trials – could determine points of doctrinal interpretation in specific cases.

Fundamentalist control of the Presbyterian Church was being diminished by altering the theological decision-making by the Presbyteries.

In 1929 the General Assembly approved a reorganization of the governing boards of Princeton Theological Seminary. As a result, exclusivist Fundamentalists were no longer in control.

J. Greshem Machen was outraged. With three other faculty members, he left to form Westminster Seminary in Philadelphia, and soon thereafter, an Independent Board of Foreign Missions. It was a counter to what he felt was a too-liberal influence in the denomination’s foreign missions program.

The General Assembly declared this competition with a denominational agency unconstitutional, and ordered all Presbyterians, including Machen, to desist from this activity. Machen refused and in 1935 he left the Presbyterian Church and formed, with some of his most militant followers, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church.

By the late 1930s, the public had become tired of the tensions between the left and right within the church. Liberal theology had prevailed, but a new wind was blowing. This time, again from Europe.

As Rogers states: “It was not a well-defined school of thought but a new movement variously called ‘dialectical theology,’ ‘neo-Calvinism,’ and ‘neo-Orthodoxy.’ Among its most prominent figures were the Swiss theologians Barth and Brunner and the American Reinhold Niebuhr.”

“Neo-Orthodoxy rejected,” says Rogers, “the evolutionary idealism of liberalism, which had taught that human beings were basically good and that, by cooperating with God, people would bring the kingdom of God on earth. In contrast, Barth and others preached about human sin and a God of judgment and grace who would have to break into human history.”

Neo-orthodoxy, which essentially came out of Liberalism, did not, however, reject the Higher Criticism concerning the Bible. According to Rogers: “The defining insight of early neo-orthodoxy was that God did not reveal information in an inspired book. God was revealed in the person of Jesus Christ. A person’s encounter with Christ in Scriptures was the work of the Holy Spirit.” By the late 1950s neo-orthodoxy was well established as the dominant theology within the Presbyterian Church.

Returning to Fosdick, in 1935 he preached a sermon at The Riverside Church called “The Church Must Go Beyond Modernism.”

In it he declared, “Fifty years ago the intellectual portion of western civilization had turned one of the most significant mental corners in church history and was looking out on a new view of the world. The church, however, was utterly unfitted for the appreciation of that view. Protestant Christianity had been officially formulated in pre-scientific days. Modernism, therefore, came as a desperately needed way of thinking. It insisted that the deep and vital experiences of the Christian soul, with itself, with its fellow, with its God, could be carried over into this new world and understood in the light of the new knowledge. We refused to live bifurcated lives, our intellect in the late 19th century and our religion in the early sixteenth century. God, we said, is a living God who has never uttered his final word on any subject.”

“The church thus had to go as far as modernism but now the church must go beyond it. Modernism is primarily an adaptation, an adjustment, an accommodation of Christian faith to contemporary scientific thinking. It started by taking the intellectual culture of a particular period as its criterion and then adjusted Christian teaching to that standard. Herein lies modernism’s shallowness and transiency: it arose out of a temporary intellectual crisis; it became an adaptation to, a harmonization with, the intellectual culture of, a particular generation. That, however, is no adequate religion to represent the Eternal and claim the allegiance of the soul. Let it be a modernist who says that to you!”

Fosdick goes on to say that modernism had been too preoccupied with intellectualism, too sentimental with the belief in the idea of human progress, that it had been too centered on the achievements of humanity, putting God in a kind of “advisory” position. And finally, that modernism had lost a moral standing-ground by being too accommodating to the prevailing culture.

“Harmonizing slips easily into compromising,” said Fosdick. “To adjust Christian faith to the new astronomy, the new geology, the new biology, is absolutely indispensable. But suppose that this modernizing process, well started, goes on and Christianity adapts itself to contemporary nationalism, contemporary imperialism, contemporary capitalism, contemporary racialism – harmonizing itself, that is, with the prevailing social status quo and the common moral judgments of our time.”

“We cannot harmonize Christ with modern culture,” said Fosdick at the end. “What Christ does to modern culture is to challenge it.”

In this sermon Fosdick never renounces Liberalism – many thought he had – or even mentions it by name. Fosdick still strongly believed in humanity and its possibilities in relation to God and still believed in the progress of Christianity as revealed by God. His 1938 book A Guide to Understanding the Bible demonstrates this. But his thinking and beliefs by this time had developed more like those of the emerging neo-orthodox theology.

Written by David Pultz, First Church Archivist, as part of an Adult Education lecture series sponsored by the Christian Education Committee, 1995-1996.

As a liberal, Harry Emerson Fosdick saw Christianity as progressive. It was also the subject of two of his books: The Modern Use of the Bible, written while he was at First Presbyterian, and A Guide to Understanding the Bible, written in the late 1930s.

John Macnab, our former pastor, in his article from The Journal of Presbyterian History says about Fosdick: “His theology found in the Christian faith basis for the liberal persuasion that progress is made in history, human nature is essentially good and responsive to education, the Kingdom of God is a possibility for earth. He was optimistic. In much of this there was naiveté and many of his answers were simplistic. But the assurance that human beings were not powerless, that things could be improved by rational, sensible people operating in good faith and with good will struck a responsive chord with the large numbers who came to hear his sermons.”

Though Fosdick considered himself a theological liberal, and remained so throughout his life, his theological outlook changed. This was particularly so in the mid-1930s.

At age seven, Fosdick asked to be baptized in the Baptist church of Westfield, NY, where his family held their membership. In his autobiography Fosdick says, “I judge from the beginning I was predestined to religion.” At that age Fosdick’s ambition was to become a missionary.

In his freshman year at Colgate University, Fosdick reports, “My retrospective picture of myself when I entered college presents a very simple-minded boy – appreciative faculties wide awake, critical faculties asleep.”

He reports that during his freshman year at Colgate his father suffered a nervous breakdown due to financial strain and consequently had to leave his teaching for a while. Young Harry took the following year off to earn money and reports that in the moments of solitude he spent that year he became acutely aware of an inner spirituality. The biographer Robert M. Miller says Fosdick was something of a mystic at heart. It was also a summer when doubts about the accuracy of the Bible began to seriously emerge in his mind.

After reading Andrew D. White’s History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom that summer, he writes in his autobiography, “Here were the facts, the shocking facts about the way the assumed infallibility of the Scriptures has impeded research, deepened and prolonged obscurantism, fed the mania of persecution, and held up the progress of mankind. I no longer believed the old stuff I had been taught. Moreover, I no longer merely doubted it. I rose in indignant revolt against it.”

These rebellious doubts produced such an intense feeling that “Intellectually,” he says, “I faced a disturbing fight, from which, as easily as not, I might have emerged minus religion.”

At one point he reports that he nearly discarded his faith altogether. It was the profound influence of Professor William Newton Clarke at Colgate, however, that “saved” his faith. He was a professor at the Theological Seminary, and his new book at the time was An Outline of Christian Theology. It brought Clarke praise among the religiously liberal clergy, and condemnation among the orthodox. Clarke was a theological liberal who showed Fosdick that the Scriptures and modern scientific discoveries and historical Biblical scholarship could be reconciled.

Fosdick remembers once walking across the campus, voicing his doubts to Clarke about the virgin birth, remarking that he could believe Jesus was spiritually divine, but not physically divine. Fosdick then reports: “’Physically divine?’ said Dr. Clarke with a quizzical inflection. There was silence for a moment and then I said: ‘That is nonsense, isn’t it?’ ‘Of course, it is nonsense,’ he answered.”

Clarke then went on to advise Fosdick that he must in effect start by seeing that any divinity in Jesus must consist in his spiritual quality.

These experiences were to profoundly influence his theology for the rest of his life.

Two other important influences on Fosdick, particularly in his Montclair ministry days (1903 – 1915), were the Christian social liberal Walter Rauschenbusch and the Quaker Rufus Jones.

Rauschenbush had written Christianity and the Social Crisis, and Jones had written some 57 books. They were both advocates of social reform from the Christian perspective.

The liberal theology of Fosdick had come out of an age of optimism. There was a technological and industrial revolution that had been going on since the late 19th century. The liberal theology of the day reflected that optimism – of humanity’s upward progress toward the good and took as its basis the most recent scientific discoveries, including the Darwinian theory of evolution and historical Biblical scholarship, coming chiefly from Germany.

In Biblical terms, this idea of progress came particularly from a close reading of Old Testament texts in the chronology in which they were understood to have been written.

In A Guide to Understanding the Bible, Fosdick lists six Biblical Ideas and shows, within a chronological arrangement of Biblical texts, how they change and progress.

They are: The idea of God, of Man, of Right and Wrong, of Suffering, of Fellowship with God, and of Immortality.

With these ideas he demonstrates how they developed and progressed as revelations from God, up to the time of Jesus. He further argues that, in a living Deity, ideas continue to progress through divine revelation. In his sermon “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” he says, “Repeatedly one runs on verses like this: ‘When he the spirit of truth is come, he shall guide you into all the truth.’ That is to say, finality in the Bible is ahead. We have not reached it. We cannot yet compass all of it. God is leading us out toward it.”

Primarily known as a preacher, Fosdick increasingly, over the years, viewed preaching as counseling on a group scale. He said he often prayed to God before each sermon to let him reach at least one person in some important way with his message.

Fosdick never saw himself as a theologian, but as a communicator and interpreter of the Gospel. Early in his educational life he thought of just teaching theology, but it was his nervous breakdown during his first year at Union Theological Seminary that, he says, was a turning point in his desires. Because of this experience, he wanted to reach people, through a personality centered ministry, involving both preaching and one to one counseling. This personal counseling involved a kind of psychological and spiritual mix. He was one of the first to advocate and practice this new approach.

Fosdick wrote nearly 40 books in his life, and it was primarily the quality of his writing that was the strength of his communicative skills. He would spend anywhere from 16 to 20 hours or more preparing a sermon. His sermons were a logical structure of ideas and illustrations.

A former student of his at Union, the Rev. Warren E. Darnell, described his preaching style this way: “There were no gestures by hand or body movement. His preaching was all done by compelling voice control delivering a reasoned message with perfect diction which moved the mind and heart of worshippers from within. His messages were powerful and unforgettable. He was always a compelling spokesman with copious knowledge and a facile mind.”

Fosdick felt a strong conviction that theologies are culturally conditioned. He argues, “Dealing as they do with eternal verities, theologians are easily tempted to assume that their formulations also are eternal, whereas, if anything on earth is tentative, subject to the push and pull of changing science and philosophy and to shifting popular moods of optimism and despair, it is systems of theologies.”

Paraphrasing his mentor, William Newton Clarke, Fosdick would say, “Astronomies change, while the stars abide.”

Fosdick felt that only on a basis of profound personal experience – God’s revelation to us on a personal level – can we find a living God. Our response to these experiences of the revelation of God’s transforming and sustaining grace is the basis of faith. “A wise theology clarifies them, reassures our faith in them, deepens our understanding of them, but, as for me, it is the experience itself in which I find my certainty, while my theological interpretations I must, in all humility, hold with tentative confidence.”

In 1935 he preached a sermon at The Riverside Church called “The Church Must Go Beyond Modernism.” Reconciling theology with science and biblical scholarship is indispensable, but we cannot, he maintained, adapt Christianity with the prevailing status quo and the prevailing moral judgments of our time. “What Christ does to modern culture is challenge it.”

There are two interesting pictures here of Fosdick. One is the modernist, the optimistic rationalist who didn’t believe in the physicality of the virgin birth; who found many of the Bible’s miracles – particularly the ones embellished in later texts – discountable. He disbelieved the Fundamentalist dogma of the inerrancy of the Bible, and the physical ascension of Christ into heaven.

It was these views that drew the accusations from his theological enemies that he was a heretic.

For Fosdick, the Bible is not so much a revelation from God, but of God. He believed that the Bible contains the word of God, not that it is the word of God, in totality.

But we see his belief in the personal, transformative experience of God as revealed in Christ. “I care little whether a man believes a Trinitarian dogma, but I care a lot whether a man has a Trinitarian experience.”

One could say that for Fosdick, excessive dogma – like creedal subscriptions – was an enemy in many ways to the spiritual life.

Fosdick believed all human attempts to define and describe God were ultimately inadequate. We can never fully define God in metaphor and symbol. They are all inadequate. He liked this quote: “God defined is God finished.”

Fosdick also despised all false images of God, particularly those that became self-justifications for ungodly actions and viewpoints.

Later in his life, in the early to mid-1960s, Fosdick was asked about the “Death of God” theologians who were momentarily in vogue, and why this was happening. His response was, “Perhaps because there are so many concepts of God that should die.”

However, he also felt that, inadequate as such concepts were, “it is far truer to think of God in terms of an inadequate symbol than not to think of him at all. The Great God is; our partial ideas of him are partly true.”

For Fosdick, the soul – or, as he often referred to it, personality – “is the most adequate symbol we have of the nature of God.”

Fosdick also saw God within these terms: A God that is love, who loves and cares for all of us, but who also is angered by sin and repulsed by evil. God is a refuge, but not an escape from our folly. God created us and gave us freedom, which we abuse, but God loves us too much to let us do evil with impunity. God gives us a choice: eternal life or death. God cares and loves us, yet we must not sentimentalize this care as a warm and fuzzy saccharine affection.

As for God’s miracles, Fosdick liked what Walt Whitman had to say: “Why, who makes much of a miracle? As to me I know of nothing else but miracles.”

For Fosdick, “The farther we get away from first hand documents of the Bible, the more marvelous the stories become.” The converse was also true. He thought that “supernatural” was a misleading word, in that the word “nature” as we think of it means the physical laws of the universe. The ancient people knew of no laws of physics, and what looked like miracles to them were not ruptures of the “normal” course of the physical world. They were instead a fulfilling of a higher law that we have yet to understand. What appears a miracle is no miracle to God.

Fosdick did not see the world as a bifurcated one with humanity and natural law on one side and God on the other, with God occasionally puncturing our natural world with the supernatural. “This is one world. God’s world throughout, whose law-abiding regularities, whose amazing artistries, whose evolution of ever higher structures, whose creation of personality, whose endless possibilities of spiritual growth and social progress indicate that it is a spiritual system. God is here, not an occasional invader of the world but its very soul, the basis of life, its under girding purpose, its indwelling friend, its eternal goal.”

For Fosdick, Jesus of Nazareth was a real man, not a myth. His Christology began with the acceptance of this fact. He was the Christ of Old Testament prophesy. As Miller says, for Fosdick, “The Scripture’s dominant conviction is not an idea but a historical deed: ‘In Christ,’” said Fosdick. “God has performed a supremely important act for the world, so climactic that prophesy found there its culmination and so determinative that all man’s future was conditioned on it.”

One thing Fosdick sought to counter was the assertion of some 19th-century scholars who wanted to radically demythologize, or discount, Jesus and his deeds and message. His last major work,

“The Man From Nazareth, as His Contemporaries Saw Him,” was a strong affirmation and defense of this central tenet.

Further, the historical Jesus for him was the humanity of Jesus. “By stating plainly that whatever questions there may be about Christ’s divinity” he said, ”there is none about his humanity.” And further, “Jesus was true man and his divinity must always be asserted and interpreted in such ways as will not cast doubt on that unmistakable fact.”

As for the divinity of Jesus, Fosdick saw in Him God’s revelation to humanity of God’s own character.

“Christ is the clearest revelation of the Divine and the noblest ideal of the human we have,” said Fosdick.

Typically, Fosdick saw Christ’s disciples as seeing Jesus in progressive stages. “At first, they may have said, God sent him. After a while that sounded too cold, as though God were the bow, and Jesus the arrow. So I suspect they went on to say, God is with him. That went deeper. Yet, as their experience with him progressed, it was not adequate. God was more than with him. So at last we catch the reverent accents of a new conviction, God came in him.”

“To put the matter simply, in Christian thinking God became Christlike. The divinity of Jesus became not only an assertion about Jesus but about divinity.” On another occasion he said, “Sometimes I think I believe in God largely because I cannot help believing in Jesus Christ.”

Fosdick saw in Christ the revelation of God, and His indwelling spirit, which for all of us, he felt, means the indwelling presence of God in our lives. “In the New Testament, Christianity is a religion of incarnation and its central affirmation is that God can come into human life.”

And yet another Fosdick quote:

“I feel in relationship to Christ like a land-locked pool beside a sea, the water in the land-locked pool is the same kind of water that is in the sea. You cannot have one sea and two kinds of sea-water. But look at the land-locked pool, little, imprisoned, soiled it may be in quality, and then look at the sea, with deeps and distances and tides and relationships with the world’s life the pool can never know.”

Later in life he wrote, “The older I grow, the more I think that I understand the cross best when I stop trying to analyze it and just stand in awe before it.”

Fosdick saw the resurrection in purely spiritual terms, however. It was another belief that earned him the charge of being a heretic. But Fosdick personally couldn’t accept the physical resurrection and didn’t think it really mattered whether one believed in it that way or in the spiritual sense.

What did matter is that without it, there was no Christian Church. As for the disciples, he said, “Those who lived most intimately with him stood most in awe of him, with mingled love and adoration acknowledged in him a divine authority, felt in him the very presence of their God, gave him the supreme name they knew to express transcendent greatness, Messiah, and after Calvary they were victoriously confirmed in their adoration of him by their faith in his resurrection and their experience of his living presence. That is the astonishing fact with which the Christian church began.”

Nothing in Fosdick’s liberal theology was more central than his belief in the worth of each human being as a child of God. When Fosdick referred to “Personality” he meant ‘Soul’.” “My personality,” he said, “is God’s most sacred trust to me; it is the thing I am, my soul.”

In his book The Assurance of Immortality, he asks: “Are we bodies that have spirits, or are we spirits that have bodies? Which is essentially the person? The Christian affirmation is not that we have souls, but that we are souls; that we substantially are spirit, as invisible as God. The affirmation of the materialist is not that we have bodies, but that we are bodies; that flesh is the essence of us, and that all our intellectual and moral life, like the peal of a bell, is a transient result of physical vibrations, and ceases when the cause is stopped. Between these two affirmations the decision lies: either we are bodies that for a little time possess a spiritual aspect, or else we are spirits using an instrument of flesh.”

Fosdick recognized that things shape our outward personality – genetic inheritance, social upbringing, culture, for instance. But he saw our essential freedom from these strictures in our spiritual nature. As the biographer Miller says, Fosdick saw that “Mankind’s spiritual nature is immune to the vicissitudes of circumstance.”

Fosdick says, “There are doors in us no man can shut. There are areas of our lives not at the mercy of man and circumstance. All the sources of a man’s liberty, independence, spiritual richness, and resources lie in his use of these inner doors that God opened, and no man can shut.”

Miller continues: “For Fosdick human nature is not absolutely fixed and human life is never static. Life is an adventure in becoming.”

“Therefore,” Fosdick says, “the deepest worth of a man is not in what he has, not in what he has done, not in what he is; it is in what he may become.”

As for sin, Fosdick disbelieved the traditional idea of original sin. He admitted that early in this century, before the advent of the First World War, his view of humanity’s capacity for sin had been muted. It was, of course, a condition of the optimism of the times that he and others of the Liberal Christian movement took this view.

After the War, and as the horrors of the 20th century unfolded, Fosdick’s view of mankind’s sinfulness found voice in his sermons.

Fosdick, however, never thought that by demonizing humanity, we elevated God. He believed in mankind, despite our sinful nature, precisely because of the great saving grace God gives to us most freely when we open ourselves up to it.

For Fosdick, mankind’s sins were a corruption of self, inborn, a universal rebellion against God. He sees us as not innocent and uncorrupted before the fall (Adam).

One of the most constant themes for Fosdick was the promise of immortality. He believed that nothing – not even death – will separate us from the Love of God.

He believed that belief in immortality was not just a reward in the hereafter, but a sacred trust for the present. “To enter here and now,” he said, “into the world of spiritual values so that truth, goodness, beauty and love are one’s very being, its substance and its glory – that is the present possession of eternal life. And to have faith that these spiritual values are no casual by-product of a negligent universe, but, rather, the very essence of the real world, and that death has no dominion over them or their possessors – that is faith in immortality.”

Written by David Pultz, First Church Archivist, as part of an Adult Education lecture series sponsored by the Christian Education Committee, 1995-1996.

In 1918, three Presbyterian Churches merged into one, taking on a long and unwieldy official name: “The First Presbyterian Church in the City of New York, Founded 1716 – Old First, University Place, Madison Square Foundation.”

The chief proponent of this merger was Arthur Curtiss James, a wealthy industrialist who was a major benefactor and a trustee of Old First.

The first service of the combined churches was held November 3, 1918, with Dr. Charles Parkhurst of Madison Square Presbyterian Church preaching. The other pastors present were Howard Duffield, of Old First, and George Alexander, of University Place Presbyterian. All three pastors were of retirement age, and two of them, Duffield and Parkhurst, retired soon afterward.

Parkhurst, in his sermon, said that all three merged churches were dead. “There were three parents in this case,” he said, “and they all died giving birth to this church – the New First Presbyterian Church.”

Each church contributed something important and unique. With the sale of the valuable property that Madison Square Church had occupied, a handsome endowment was procured. University Place Presbyterian Church had a sizable congregation, and Old First had the best location and building size, as well as a long and venerated history. Our former pastor John Macnab said once, tongue firmly in cheek, that the combining of these three important elements was an unusually wise decision for Presbyterians. One of our Elders, Eric Hilton, has said that he firmly believes that were it not for this merger, this congregation would not be in existence today.

At a meeting on January 8, 1919, of the committee appointed to select a new pastor, it was told to those present that Dr. John Timothy Stone of Fourth Presbyterian Church in Chicago had declined the offer to become minister here, and that Harry Emerson Fosdick had also declined, saying he did not want to attend to administrative duties. He only wanted to preach. The realization came that no one pastor could manage all the duties required for such a large and vital congregation.

A novel approach was then suggested. George Alexander was to become senior minister, with Fosdick as associate preaching minister and Thomas Guthrie Speers as another associate. Speers had also come from the University Place Church and was to preach at the evening services and also handle the administrative duties. Alexander was 74, Fosdick was 41 and Speers was 28.

Fosdick wrote in his autobiography: “It was very attractive, I had had four years at large without a parish, the thought of having again my own congregation, with an opportunity for consecutive ministry and the chance to combine the two vocations I had always cared for most. I told the church that I knew nothing about Presbyterian law, that they must take full responsibility on that score, but that if such an arrangement as they suggested were permissible, I would accept.”

And he did accept. The unusual and progressively ecumenical (for the time) arrangement was enthusiastically supported by the congregation and presbytery.

The installation of the three was held on Wednesday, January 29, 1919. Dorothy Fowler, in her history of First Church, A City Church, says that Fosdick anticipated many years of service, combining two activities he most enjoyed: preaching and teaching.

In his autobiography, The Living of These Days, Fosdick says of his fellow ministers: “Dr. George Alexander was one of the most admirable and lovable men I ever knew and my relationships with him were completely satisfying. Along with Guthrie Speers, our colleague, we made a harmonious team.”

Dorothy Fowler writes, “The church was jammed with every pew rented. Fosdick’s early sermons were in no way controversial; he did not discuss complex theological questions. His emphasis was always on Jesus Christ. He felt religion had become involved in too many entanglements, that Christianity was simply Christ. Although some people preferred elaborate theological excursions, as Fosdick viewed matters, the important thing was the life of Christ as a way of life. He emphasized an individual’s relation to God and Christ.”

In his first year here, Fosdick’s sermons dealt in many instances with World War I. Former Pastor John Macnab writes, in an article in The Journal of Presbyterian History, that “for eight months, beginning in 1918, every sermon made extended reference to the war.” Fosdick’s support of American participation in the war began as early as 1914, and his support for the war was strong by November of 1918.

Macnab continues, “he was a one theme preacher, undoubtedly evidencing some of the inner struggle he was experiencing. His mind was changing.” Fosdick’s position was not unusual, however. Preachers throughout the country were almost of one mind in declaring the war a holy one. At Fosdick’s first parish, the Montclair (NJ) Baptist Church, he had preached a sermon, “Things Worth Fighting For.” He later called it “atrocious.” His 1917 book, The Challenge of the Present Crisis, defended war. It was the only book, he later said, he wished he had not written. Gradually, however, he stressed the need for reconstruction and particularly the need for the League of Nations as a way to avert another war. When the country stayed out of the League and retreated into isolationism, Fosdick became an ardent pacifist. He remained so for the rest of his life.

By the spring of 1919 it had become evident that First Presbyterian was too small to accommodate the crowds that had come to attend service. The choir loft to the west was then added, and the gallery on the eastern side where the choir used to be was used for more seating. Also, the door to the Eleventh Street building, the South Wing, as it is now called, was enlarged, seating another 200 people.

In the summer of 1921 Fosdick visited missions in China and Japan. He addressed several conferences and was disturbed by the divisions within the missionaries. There were essentially two camps: Fundamentalists in one and those of more liberal theological beliefs in the other. Says Fowler: “Instead of cooperating in the mission field the fundamentalists concentrated on attacking their liberal brethren.” “This experience may have influenced him,” says Fowler, “in his choice of title for his sermon – which rather than the contents was a gauntlet thrown down to the fundamentalists.”

The sermon was a plea for tolerance, and in it Fosdick argued for a church, as he says in his autobiography, “inclusive enough to take in both liberals and conservatives without either trying to drive the other out.”

His emphasis, however, pointed toward the Fundamentalists as the offending party. “These two groups exist in the Christian churches and the question raised by the Fundamentalists is: shall one of them drive the other out? Will that get us anywhere?” He effectively repeats this rhetorical question in slightly varied form after each argument for a different interpretation of three of the five “fundamentals”: the virgin birth, the inerrancy of the Bible, and the second coming of Christ.

Although the sermon was essentially a plea for tolerance, Fosdick did not mince words in defining the gulf of difference between the liberal and Fundamentalist theological points of view. “Too often,” he said, “we preachers have failed to talk frankly enough about the differences of opinion which exist among evangelical Christians, although everybody knows they are there.” He criticized the Fundamentalists, saying, “If they had their way, within the church, they would set up in Protestantism a doctrinal tribunal more rigid than the Pope’s.”

After explaining Christian liberals’ efforts to reconcile the Bible with the new scientific knowledge, he says: “the Fundamentalists are out on a campaign to shut against them the doors of Christian fellowship. Shall they be allowed to succeed?”

And at another point, after arguing the liberal interpretation on the virgin birth, he says: “the question which the Fundamentalists raise is this: shall one of them throw the other one out? Has intolerance any contribution to make in this situation?”

Fosdick, however, differentiates between Fundamentalists and Conservatives, saying, “All Fundamentalists are conservatives, but not all Conservatives are Fundamentalists.” In a further expansion to this tone of reconciliation, he later says, addressing those of the younger generation: “if some young, fresh mind here is tempted to be intolerant about old opinions, offensively to condescend to those who hold them and to be harsh in judgment on them, he may well remember that people who held these old opinions have given the world some of the noblest character and the most rememberable service that it ever has been blessed with.”

But as much as he pleads for an inclusive church, he has at the same time harsh and biting words for the exclusivist Fundamentalists.

At one point, making a plea for intellectual openness and Christian freedom, he says, “Science treats a young person’s mind as if it were really important. A scientist says to a young person: Come, study with us! See what we already have seen and then look further to see more, for science is an intellectual adventure for the truth. Can you imagine anyone who is worthwhile turning from that call to the church, if the church seems to say, ‘Come, and we will feed you opinions from a spoon. These prescribed opinions we will give you in advance of your thinking; now think, but only so as to reach these results.’ You cannot challenge the dedicated thinking of this generation to these sublime themes upon any such terms as are laid down by an intolerant church.”

“Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” was thus a plea for tolerance, deeply critical of those unwilling to accept, as Christians, others with different Biblical interpretations.

Fosdick’s plea for tolerance was meant to go beyond the walls of First Presbyterian Church. But the effectiveness with which it did go beyond the Church was totally unexpected. Ivy Lee, a public relations agent for the Rockefellers, published, with Fosdick’s permission, a slightly edited version of the sermon with a new title: “The New Knowledge and the Christian Faith.” It was mailed to all Presbyterian clergy in the country, about 130,000 copies.

It was also reprinted in at least three religious publications: The Christian Century, The Baptist, and Christian Work.

The result was the eruption of a fierce controversy that eventually ended in Fosdick’s resignation from First Church. Later, in his autobiography, Fosdick says, “If ever a sermon failed to achieve its object, mine did.”

“The conflict between liberal and reactionary Christianity had long been moving toward a climax.”

One criticism of the sermon, coming from the other pastors at Old First, was that the title sounded like a call to do battle. Conservatives and Fundamentalists reacted to the sermon not as a plea for good will among Christians, but as heresy, and a supreme challenge to their faith. Macnab writes, “The conservatives read his words as a challenge they could only accept. They responded with militant vigor.”

Fosdick explained the controversy this way: “The conflict between liberal and reactionary Christianity had long been moving toward a climax.”

Fosdick continues: “There were faults on both sides. The Modernists were tempted to make a supine surrender to prevalent cultural ideas, accepting them wholesale, and using them as the authoritarian standard by which to judge the truth or falsity of classical Christian affirmations.”

“The reactionaries,” he says, “sensing the peril in this shift of authority, were tempted to retreat into hidebound obscurantism, denying the discoveries of science and insisting on the literal acceptance of every Biblical idea, which even Christians of the ancient church had avoided by means of allegorical interpretation.”

The Philadelphia Presbytery met on October 16, 1922, in a special session. One of its members, Clarence E. Macartney, was a pastor in Philadelphia and an ardent Fundamentalist. He proposed at this special session to make an overture to the next General Assembly meeting in May 1923 to “direct the Presbytery of New York to take such action as will require the preaching and teaching in the First Presbyterian Church of New York City to conform to the system of doctrine taught in the Confession of faith.”

At the General Assembly in Indianapolis, in May of 1923, William Jennings Bryan was dealt an initial setback by losing the vote to be moderator to Charles Wishart, president of the College of Wooster, by 24 votes.

A committee report recommended against the proposal of the Philadelphia Presbytery. But despite this, and because of speeches by Bryan and Macartney, the proposal passed by a vote of 439 to 359.

The proposal not only directed the New York Presbytery to bring the preaching at Old First into conformity, it was also told to report in full its efforts in this direction in transcript form to the General Assembly of 1924.

A day after the vote, Fosdick handed in his resignation to the Session of First Church, writing, “The action of the General Assembly is such as to present to the Presbytery of New York and to the Session of the Church a perplexing problem which centers around my preaching. I wish you to have my resignation in your hands so that the Session may act upon it at any time, severing my relations with the Church.”

Ten days later, on June 3, the Session replied, refusing to accept the resignation.

The move by the Presbytery of Philadelphia against Fosdick was, in essence, a move against the New York Presbytery. It was an attempt to force the Presbytery to conform to the strict orthodoxy of Fundamentalist theology. Fosdick was targeted as the way through which they could do it.